How Pact works

Remember these definitions from the introduction:

- Consumer: An application that makes use of the functionality or data from another application to do its job. For applications that use HTTP, the consumer is always the application that initiates the HTTP request (eg. the web front end), regardless of the direction of data flow. For applications that use queues, the consumer is the application that reads the message from the queue.

- Provider: An application (often called a service) that provides functionality or data for other applications to use, often via an API. For applications that use HTTP, the provider is the application that returns the response. For applications that use queues, the provider (also called producer) is the application that writes the messages to the queue.

A contract between a consumer and provider is called a pact. Each pact is a collection of interactions. Each interaction describes:

- For HTTP:

- An expected request - describing what the consumer is expected to send to the provider

- A minimal expected response - describing the parts of the response the consumer wants the provider to return.

- For messages:

- The minimal expected message - describing the parts of the message that the consumer wants to use.

The first step in writing a pact test is to describe this interaction.

Consumer testing

Consumer Pact tests operate on each interaction described earlier to say "assuming the provider returns the expected response for this request, does the consumer code correctly generate the request and handle the expected response?".

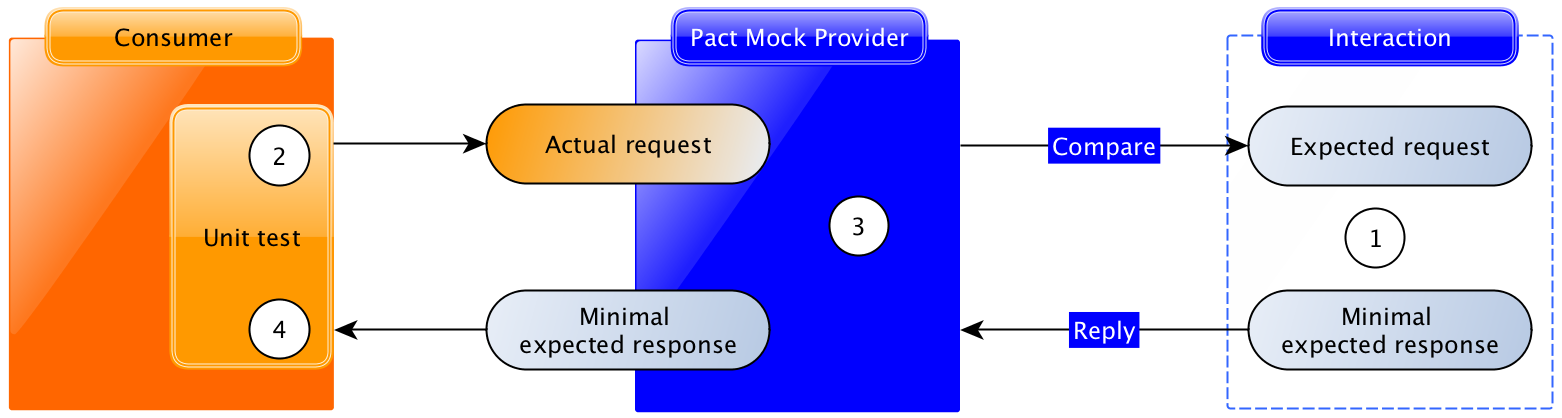

Each interaction is tested using the Pact framework, driven by the unit test framework inside the consumer codebase:

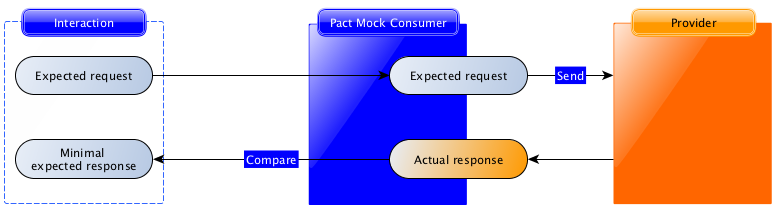

Following the diagram:

- Using the Pact DSL, the expected request and response are registered with the mock service.

- The consumer test code fires a real request to a mock provider (created by the Pact framework).

- The mock provider compares the actual request with the expected request, and emits the expected response if the comparison is successful.

- The consumer test code confirms that the response was correctly understood

Pact tests are only successful if each step completes without error.

Usually, the interaction definition and consumer test are written together, such as this example from this Pact walkthrough guide:

# Describe the interaction

before do

event_api.upon_receiving('A POST request with an event').

with(method: :post, path: '/events', headers: {'Content-Type' => 'application/json'}, body: event_json).

will_respond_with(status: 200, headers: {'Content-Type' => 'application/json'})

end

# Trigger the client code to generate the request and receive the response

it 'is successful' do

expect(subject.save_event(event)).to be_true

end

Although there is conceptually a lot going on in a pact interaction test, the actual test code is very straightforward. This is a major selling point of Pact.

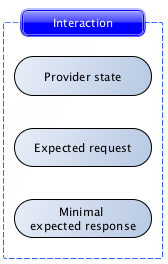

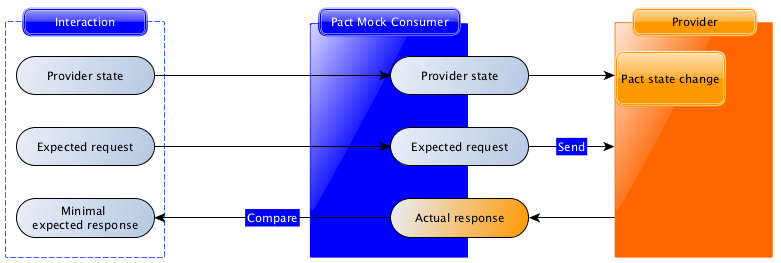

In Pact, each interaction is considered to be independent. This means that each test only tests one interaction. If you need to describe interactions that depend on pre-existing state, you can use provider states to do it. Provider states allow you describe the preconditions on the provider required to generate the expected response - for example, the existence of specific user data. This is explained further in the provider verification section below.

Instead of writing a test that says “create user 123, then log in”, you would write two separate interactions - one that says “create user 123”, and one with provider state “user 123 exists” that says “log in as user 123”.

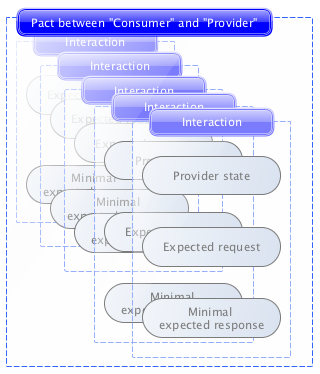

Once all of the interactions have been tested on the consumer side, the Pact framework generates a pact file, which describes each interaction:

This pact file can be used to verify that the provider meets the consumer's expectations.

Provider verification

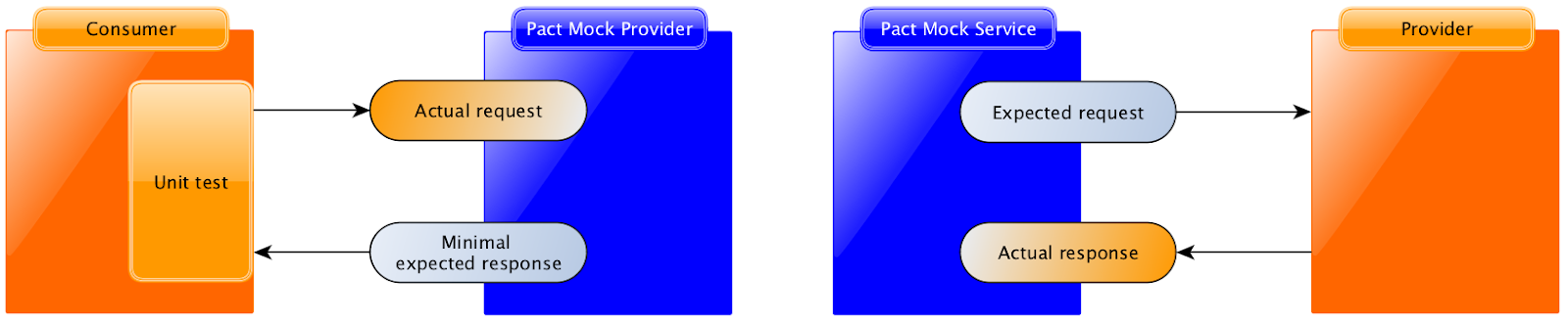

In contrast to the consumer tests, provider verification is entirely driven by the Pact framework:

In provider verification, each request is sent to the provider, and the actual response it generates is compared with the minimal expected response described in the consumer test.

Provider verification passes if each request generates a response that contains at least the data described in the minimal expected response.

In many cases, your provider will need to be in a particular state (such as "user 123 is logged in", or "customer 456 has an invoice #678"). The Pact framework supports this by letting you set up the data described by the provider state before the interaction is replayed:

Putting it all together

Here’s a repeat of the two diagrams above:

If we pair the consumer test and provider verification process for each interaction, the contract between the consumer and provider is fully tested without having to spin up the services together.

Non-HTTP testing (Message Pact)

Modern distributed architectures are increasingly integrated in a decoupled, asynchronous fashion. Message queues such as ActiveMQ, RabbitMQ, SNS, SQS, Kafka and Kinesis are common, often integrated via small and frequent numbers of microservices (e.g. lambda). These sorts of interactions are referred to as "message pacts".

There are some minor differences between how Pact works in these cases when compared to the HTTP use case. Pact supports messages by abstracting away the protocol and specific queuing technology (such as Kafka) and focusses on the messages passing between them.

Check our feature support to ensure your language has this capability.

info

To reiterate: Pact does not know about the various message queueing technologies - there are simply too many! And more importantly, Pact is really about testing the messages that pass between them, you can still write your standard functional tests using other frameworks designed for such things.

When writing tests, Pact takes the place of the intermediary (MQ/broker etc.) and confirms whether or not the consumer is able to handle a given event, or that the provider will be able to produce the correct message.

How to write "message pact" tests?

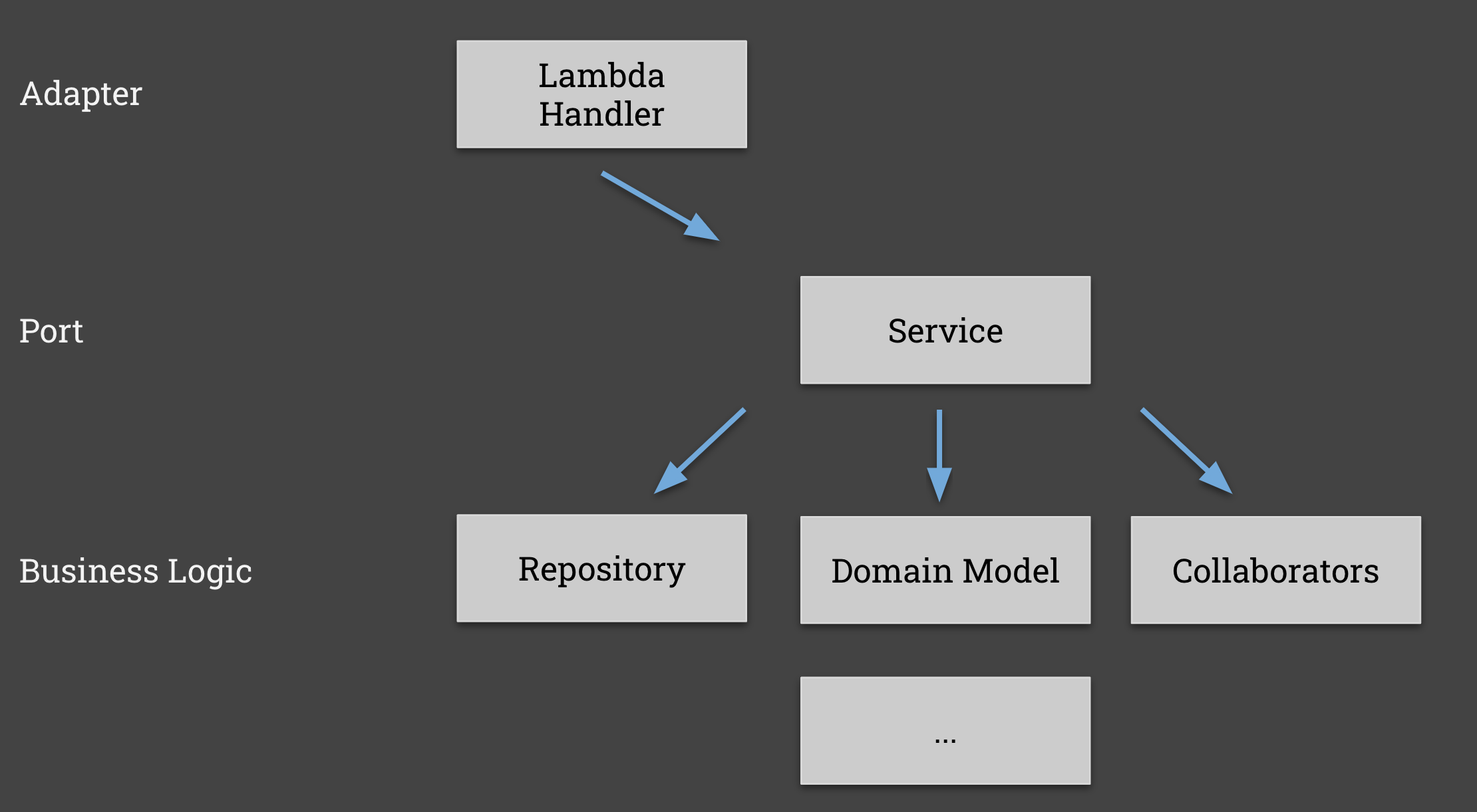

We recommend that you split the code that is responsible for handling the protocol specific things - for example an AWS lambda handler and the AWS SNS input body - and the piece of code that actually handles the payload.

You're probably familiar with layered architectures such as Ports and Adaptors (also referred to as a Hexagonal architecture). Following a modular architecture will allow you to do this much more easily:

Let's walk through an example using a product event published through AWS SNS as an example.

Consumer side

The consumer expects to receive a message of the following shape:

{

"id": "some-uuid-1234-5678",

"type": "spare",

"name": "3mm hex bolt",

"version": "v1",

"event": "UPDATED"

}

With this view, the "Adapter" will be the code that deals with the specific queue implementation. For example, it might be the lambda handler that receives the SNS message that wraps this payload, or the function that can read the message from a Kafka queue (wrapped in a Kafka specific container). Here is the lambda version:

const handler = async (event) => {

console.info(event);

// Read the SNS message and pass the contents to the actual message handler

const results = event.Records.map((e) => receiveProductUpdate(JSON.parse(e.Sns.Message)));

return Promise.all(results);

};

The "Port" is the code (here receiveProductUpdate) that is unaware of the fact it's talking to SNS or Kafka, and only deals in the domain itself - in this case the product event.

const receiveProductUpdate = (product) => {

console.log('received product:', product)

// do something with the product event, e.g. store in the database

return repository.insert(new Product(product.id, product.type, product.name, product.version))

}

This function is the target of the Pact test on the consumer side.

Provider (Producer) side

On the other side, we need to find the "Port" that is responsible for producing the message. In our case, we have a ProductEventService that is responsible for this:

class ProductEventService {

async create(event) {

const product = productFromJson(event);

return this.publish(createEvent(product, "CREATED"));

}

async update(event) {

const product = productFromJson(event);

return this.publish(createEvent(product, "UPDATED"));

}

...

async publish(message) {

const SNS = new AWS.SNS({

endpoint: process.env.AWS_SNS_ENDPOINT,

region: process.env.AWS_REGION

});

const params = {

Message: JSON.stringify(message),

TopicArn: TOPIC_ARN,

};

return SNS.publish(params).promise();

}

}

The publish is the bit ("Adapter") that knows how to talk to AWS SNS, the update is the bit ("Port") that just deals in our domain and knows how to create the specific event structure. This is the function on the provider side that we'll test is able to produce the correct message structure.

Further Reading

Take a look at an example consumer project and its example provider project to see this in action.

Next steps

Contract tests should focus on the messages (requests and responses) rather than the behaviour. It can be tempting to use contract tests to write general functional tests for the provider. Experience shows this to leads to painful experiences with brittle tests. See this guide for contract testing best practices.

Pact tests should be data independent. Pact tests are best when successful verification doesn’t depend on the specific data that the provider returns. See this guide for best practices when describing interactions.

Use the broker to integrate Pact with your CI infrastructure. Integrating Pact with your continuous integration infrastructure is a major win for safe and successful deployment. See this guide for Pact integration best practices